For a descendant of post-Civil-War immigrants from Germany, finding slavery in your family tree is pretty shocking. Granted, this discovery came on my husband’s side of the family, but that makes it no less difficult to learn. Most of his relations were from the North, and the few relations from Virginia moved to the North well before the Civil War. With all this research, finding slavery came as quite a surprise–especially, where I found it–in Hunterdon County, New Jersey.

This is just one part of the problem that plagues our country to this day. Growing up in the North, I was taught that slavery was a Southern thing. It was not our fault. It was a “them, not us” mentality. Many of our Northern ancestors even risked and gave their lives to end the appalling institution. But this story-line, which I was taught as truth, is actually fraught with omission.

Our collective Northern ancestors did a pretty good job of whitewashing the ugly truth. In some Northern states, and in New Jersey in particular, at least some of our ancestors bought, kept, and sold human beings as property and benefited from this financially. Although most people were not slave owners, some Northern states did much more than simply tolerate slavery. Instead, they actually enacted laws to support its perpetuation and also reaped financial rewards.

By discussing my new understanding, I am not trying to lessen the contributions that so many Americans made to the cause of equality. I am not diminishing:

- the conviction of pre-Civil War abolitionists or

- those who risked there own lives to help free slaves or

- those who fought to guarantee persons of color their freedom or

- those who advocated among their neighbors or at the statehouses to help change people’s attitudes or

- the countless other efforts of forward-thinking people to ensure that persons of all colors could call themselves free.

Nonetheless, there is a lot more “on us” than most of us Northerners have been taught to believe. So as one small step toward helping descendants of former slaves discover their own roots, I am sharing what I know of Nehemiah Dunham and the Dunham slaves of Hunterdon County, New Jersey. I can’t claim that the old records reveal that much. But I am putting this out there with the hope that someday, someone may find it useful.

The Long Road to Ending Slavery in New Jersey

To understand what was going on with the Dunham slaves, I found it helpful to understand the landscape of the slavery laws in New Jersey. New Jersey condoned slavery well after other Northern states had abolished it. Furthermore, it certainly did not choose to go “cold-turkey” when it came to abolition. Instead, the process was gradual–dragging on over more than half a century. Understanding New Jersey’s route to outlawing slavery provides insight into the transactions and records surrounding Dunham slaves.

Going back to the earliest days of the colony, New Jersey’s primary concern regarding the question of freedom for slaves was that they not become a burden to their communities. Historically, New Jersey’s laws made it financially burdensome for slave-owners to manumit their slaves. See, e.g., The State v. Emmons (Habeus Corpus of negro Richard) and The State v. Matthias Cramer (Habeus Corpus of negro Phebe) 2 N.J.L. 10 (N.J. Sup. Ct. May 1806) (Kilpatrick, J.) (explaining “it is found by experience that free negroes are an idle slothful people, and prove very often chargeable to the place where they are . . . .”).

For example, under New Jersey’s 1713-14 act, “every master manumitting his slave shall give security to the Queen, in the sum of 200 pounds, that he will pay yearly to the slave so to be manumitted, the sum of 20 pounds.” Id. By 1769, the 200-pound security continued, but the 20-pound yearly maintenance payment was converted to an obligation “to indemnify the township against all charges of maintenance, in case his slave so to be manumitted, shall become chargeable.” Id. Failure to do any of these things would void the manumission.

Yet a concern for the burden on the community was not the only motivating factor. New Jersey also recognized and supported the benefits that New Jersey communities received from slave labor. By 1786, New Jersey began to officially acknowledge the need to end slavery in the State. But that need did not yet outweigh the “sound Policy” of affording “ample Support to such of the Community as depend upon [slave] Labour for their daily Subsistence.” (“An Act to prevent the Importation of Slaves into the State of New-Jersey, and to authorize the Manumission of them under certain Restrictions, and to prevent the Abuse of Slaves,” Acts 10th G.A. 2nd sitting, ch. CXIX, at 239-42 (March 2, 1786).)

1786

Even so, New Jersey’s March 2, 1786 act was a critical step toward abolition.

- The 1786 act made it illegal to bring into the State for Sale or for Servitude “any Negro Slave brought from Africa since the year [1776].” (Sect. 1.)

- The 1786 act did not impose an outright ban on the slave trade in New Jersey. It allowed owners of slaves brought from Africa before 1776 or slaves not born in Africa to be brought into New Jersey for sale or purchase subject to a 20-Pound forfeiture for each such slave. (Sect. 2.)

- Furthermore, the 1786 act allowed slave owners to move into New Jersey with their slaves as long as the slaves were not brought from Africa after 1776. (Sect. 3.)

- It also encouraged manumission by removing financial penalties previously associated with freeing slaves. Slaves could be manumitted without payment of a settlement (the owners were exonerated from all charges and costs), but only if the slaves were between 21 and 35 years old. (Sect. 5.)

- The act also banned freed slaves in other states from coming into New Jersey.

The provisions of the 1786 act reflect New Jersey’s long-held concerns regarding the support and maintenance of freed slaves. Limitation of the slave trade in 1786 nonetheless paved the way for New Jersey’s first significant move toward abolition.

1804

It wasn’t until 1804 that the New Jersey Legislature put its first significant limitation on the property rights of slave owners. On February 15, 1804, the New Jersey Legislature passed “An act for the Gradual Abolition of Slavery.” (P.L. 1804, chap. CIV, p. 251.) While the title and first sentence of the act suggest appeasement of abolitionists, the statutory text actually maintains the practice and reflects the continued influence of the slave holders in New Jersey. The act’s preamble promises that “every child born of a slave within this state, after the fourth day of July next, shall be free . . .”

Despite their “free” status, however, each child born of a slave after July 4, 1804, would have to remain the servant of the mother’s owner until he or she turned 25 years (males) or 21 years (females).

The 1804 act also required registration of birth for all children of slaves by “the person entitled to the service of a child.” So after 1804, children born to slaves could not be owned, but they must be registered and still owed a 20+ year obligation of service. These people technically became what is known as “servants for years,” but were understood by the general public to be “slaves for a term.” James J. Gigantino II, The Ragged Road to Abolition: Slavery and Freedom in New Jersey 1775-1865, 96 (U. Penn. Press 2016).

1846

Slavery was technically “abolished” by the New Jersey Legislature in its April 18, 1846 “An Act to Abolish Slavery” (Revision of 1846, Title XI, chap. 6, p. 382-390). The 1846 act again began with the language of freedom.

1. BE IT ENACTED by the Senate and General Assembly of the State of New Jersey, That slavery in this state be and it is hereby abolished, and every person who is now holden in slavery by the laws thereof, be and hereby is made free, subject, however, to the restrictions and obligations hereinafter mentioned and imposed; and the children hereafter to be born to all such persons shall be absolutely free from their birth, and discharged of and from all manner of service whatsoever.

Yet once again, this law fell short of eliminating slavery in New Jersey. The “restrictions and obligations . . . mentioned and imposed” on these newly-freed people reflected New Jersey’s continued unwillingness fully discontinue the economic benefit of slaves to their owners.

In reality, newly-freed slaves became apprentices, “bound to service to his or her present owner” until discharged. (Sect. 2.)

Furthermore, while all children born to apprentices were now free, they needed to be supported and maintained by the master or mistress of such apprentice until they attained the age of six years. Upon that age, any maintenance obligation stopped and the children were to be “bound out by the trustees or overseers of the poor, as in other cases of poor children” with the master or mistress “being first entitled to take such children under indentures.” (Sect. 9.) Placement of the six-year-old child, however, with the child’s apprentice parent was far from guaranteed.

1865

New Jersey’s slavery-through-apprentice system was finally outlawed at the conclusion of the Civil War with the ratification of the 13th Amendment to the United States Constitution on December 6, 1865. In fact, New Jersey rejected ratification on March 16, 1865, and only voted in favor of ratification on January 23, 1866–after the 13th Amendment went into effect.

The reasons why the people of New Jersey allowed slavery for so long are beyond my 21st-century comprehension. Many well-researched articles and books have tried to tackle this question. In one such book, cited above, Professor James Gigantino, discusses the economic and political forces at work after the Revolutionary War, including rebuilding New Jersey’s devastated post-war economy. The Ragged Road, at 62-65. He also points to the Revolution itself and New Jersey’s role in selling slaves of loyalists as entrenching slavery in New Jersey’s consciousness.

Hunterdon County’s Role

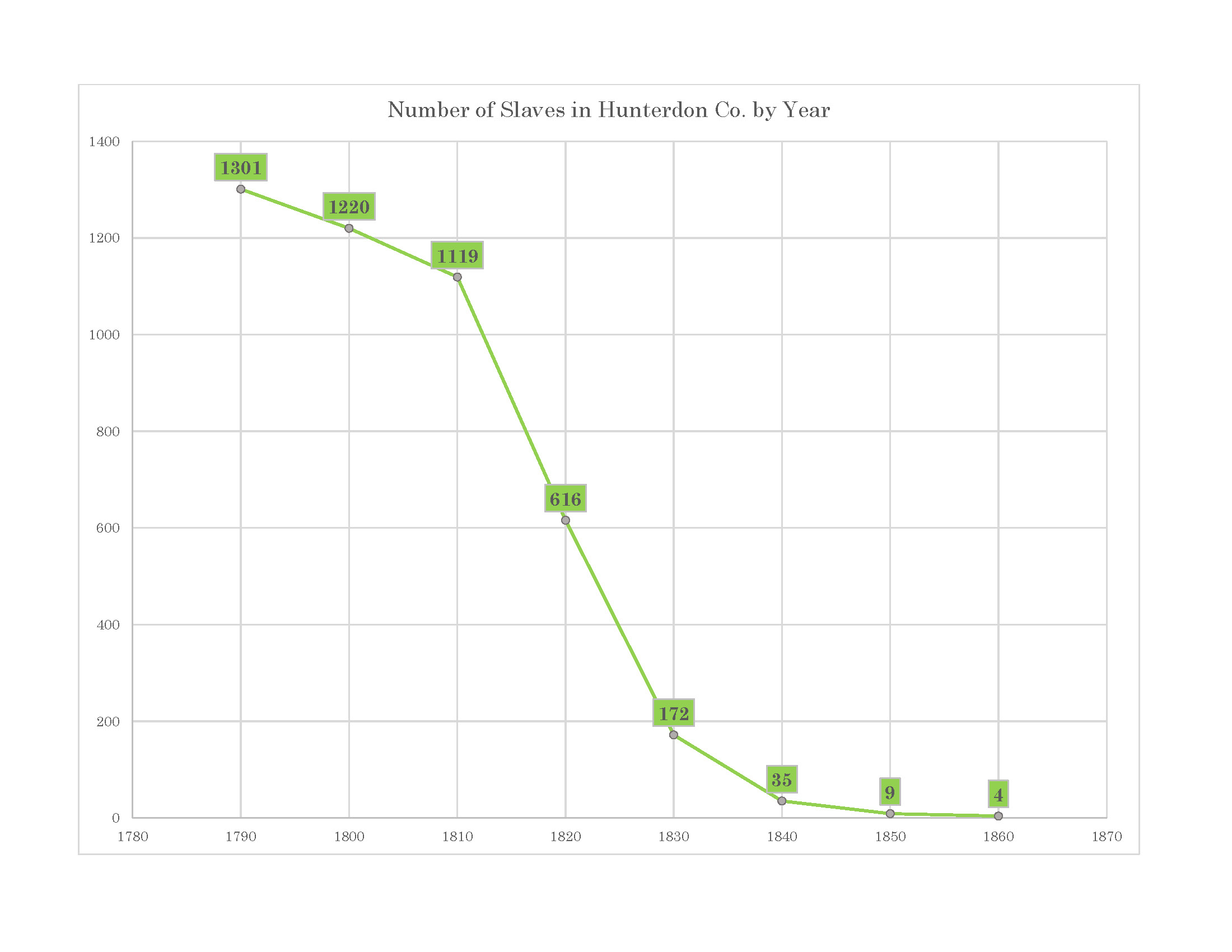

Hunterdon County residents played a part in slavery’s continuation after the Revolution. Many, but not most, of Hunterdon County’s residents owned slaves. In 1988, historian Giles Wright assembled comprehensive statistics regarding the number of slaves and free African Americans in New Jersey since 1790. Giles R. Wright, Afro-Americans in New Jersey a Short History, at Appx. 3 (N.J. Hist. Comm’n, Dept. of State 1988). Although Wright’s statistics have been more recently criticized as understating the number of slaves after 1804, they are still helpful to examine the relative numbers of slaves in Hunterdon County by decade.

Hunterdon County had 1301 slaves in 1790. According to Wright, New Jersey’s slave population peaked in 1800 at 12,422 slaves state-wide. See Afro-Americans in New Jersey, at 25. Unlike some other nearby counties, including Somerset and Middlesex, Hunterdon’s slave population actually declined slightly from 1790 to 1220 slaves by 1800. The number of slaves in Hunterdon County saw the greatest decline during the 1810 decade, going from 1119 slaves to 616 slaves in 1820.

Post-Revolution, as New Jersey rebuilt and industrialized, the “use of slaves in nonagricultural occupations became popular.” The Ragged Road, at 69. An example provided by Gigantino in his book illustrates this point. The “Andover Iron Works and the Union Iron Works in Hunterdon County both used slave labor.” Id.

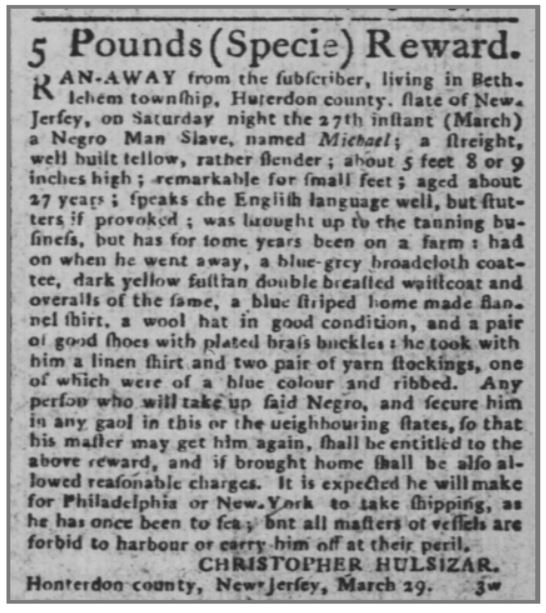

At New Jersey’s height of slavery, in the late 1700s and into the early 1800s, advertisements, for both slave sales and runaway slaves, were common in New Jersey and Pennsylvania.

These advertisements are now a helpful record allowing us to know a little bit more about the lives and stories of the mentioned slaves.

To illustrate how these stories can be told, I turn back to Professor James J. Gigantino. In his 2010 University of Georgia dissertation entitled “Freedom and Unfreedom in the ‘Garden of America:’ Slavery and Abolition in New Jersey, 1770-1857,” Professor Gigantino tells an interesting story of a slave named Catherine from Hunterdon County, which supports the continued presence of slavery well after 1804. (He also tells this story in the Ragged Road.) He pieces together Catherine’s life from various birth records, census records and bills of sale. Through her children and ultimately herself, Catherine’s story illustrates the effects of both the 1804 and 1846 acts, which abolished slavery in name, but not in practice.

According to Gigantino, Catherine, called “Cate,” was born as a slave to John Hagaman in Hunterdon County in 1789. Id. at 1. Due to New Jersey’s 1804 law requiring registration of all children of slaves by the person entitled to the service of a child, Hagaman filed two birth records for Cate. In 1811, she had a boy named Bob. In 1815, Cate gave birth to a daughter Hannah. By law, both Bob and Hannah were servants of John Hagaman until the ages of 25 and 21 respectively. Thus, both would obtain their freedom in 1836.

Gigantino then details Catherine’s status as a “slave-for-life” into the 1850s:

By 1840, Catherine, without her children living with her, moved with her master to the neighboring town of Raritan. Curiously, after another ten years with Hagaman, the 1850 census recorded Catherine, now sixty-two, as a free woman. Somehow then, she had seemingly righted the unequal balance between slave and free. However, six years later, on February 16, 1856, Hagaman sold sixty-seven year old Catherine, his “slave for life,” for twenty dollars to Charles Sutphin of Sommerville as Hagaman prepared to move with his son Dennis and daughter-in-law Mary to Joshua, Illinois, forty miles west of Peoria.

Id. at 2. (Citing Bill of Sale, John Hagaman to Charles Sutphin, February 16, 1856 regarding “slave for life” Catherine, Hunterdon County Slave Births, Manumissions, and Miscellaneous Records, HCHS. United States Census Schedules, 1830, 1840, 1850, 1860 for Amwell, New Jersey, Raritan, New Jersey, and Joshua, Illinois.)

Unfortunately, Gigantino cannot trace Catherine’s children, Bob and Hannah, past the initial Hunterdon birth records. Id. at 9. They are not listed as slaves in the 1830 census. He speculates that they could either have been sold away or died before they exited slavery. Id. (citing a statistic that 54% of American slaves died before they reached age 25). In his book, the Ragged Road, he blames the “equation of slaves for a term with slavery and not apprenticeship” as the primary reason slaveholders were still allowed to sell slave children–because “their parents had no legal right to stop them.” The Ragged Road, at 101.

While the number of slaves decreased as the Civil War approached, historians emphasize the lingering opposition to Republican ideals. Both New Jersey and Hunterdon County voted against the Republicans and their Republican Presidential candidate Abraham Lincoln. In fact, New Jersey overall, along with Hunterdon County, “voted against Abraham Lincoln both immediately before and even during the Civil War.” Linda Salouskos, “Hunterdon County not a ‘bastion of abolitionism’ during the Civil War,” Hunterdon Review (Nov. 6, 2007) (discussing presentation by amateur historian John Kuhl). In his presentation, “Kuhl also displayed a newspaper advertisement offering a 23-year-old male slave for sale in Flemington in 1859.” Id.

That slavery continued, albeit at low levels, in Hunterdon County in some form into the 1850s is now fairly accepted. Telling the stories of those slaves through historical records is where historians seem to be focusing their efforts. E.g., Gigantino, supra, and Lois Crane Williams, “The Last Slave in Franklin Township.” 51 Hunt. Hist. Nwsltr. 1 at 1203 (2015). It is in that spirit that I am adding to the stories of the Hunterdon County slaves based on information I have discovered in my own family research.

Nehemiah Dunham

My research brought me to the realization that the Dunham family owned slaves through my review of Nehemiah Dunham’s will.

A little background on Nehemiah Dunham seems appropriate. Dunham is generally regarded as an influential early resident of Hunterdon County. He was born to Edmund Dunham and Dinah Fitz Randolph on November 1, 1721, in Piscataway, New Jersey. As an adult, he became an early settler of Hunterdon County. He bought 600 acres of land and came to Clinton, Hunterdon County from Piscataway in about 1760.

According to the Town of Clinton, New Jersey website: “Nehemiah Dunham and his brothers, Daniel and Stephen, bought from [Jonathan] Robeson all the rest of his land on the west side of the river, except 100 acres which Robeson sold to Francis Quick, Jr., a tanner. One of the lots the Dunhams bought was known and described as the Limestone Lot. This was all of the land on the north side of what is now West Main Street to a point about opposite Hancock Street; this lot contained 51 acres. Daniel Dunham owned 20 acres on the south side; this was known as Daniel Dunham’s meadow lot, and his farm was north of West Main Street, west of the Limestone Lot, and contained 196 acres. Nehemiah Dunham owned a large tract of 383 acres. Stephen Dunham owned 100 acres on the south side of West Main Street.” http://www.clintonnj.gov/history_main.html (last visited Jan. 2, 2018).

Dunham was a cattle dealer and is known as a “famous character in his day.” Samuel Harden Still, “Historic Guide Posts,” Plainfield, New Jersey, Courier-News at 5 (Apr. 25, 1933). Under a June 5, 1777 act of the General Assembly, Dunham was appointed as a Commissioner in Hunterdon County to “administer the free and general pardon for offenders who voluntarily come forward to take and subscribe the oaths or affirmations to the State for restoration of rights of Freemen.” Thus, Dunham was responsible for pardoning loyalists who may have fought for or assisted the British.

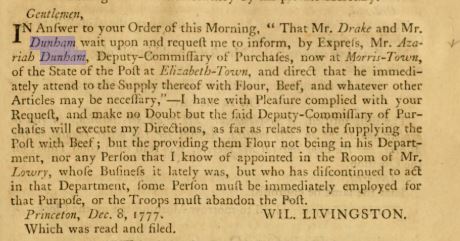

Dunham himself was then elected to the General Assembly. He served as a member of New Jersey’s General Assembly and arranged supplies for the troops. See, e.g., Votes and Proceedings of the General Assembly of New Jersey at 40-41, 43 (1777). As shown by the General Assembly records, he also interacted directly with Governor William Livingston regarding troop supplies.

As an aside, Azariah Dunham is Nehemiah Dunham’s cousin. Azariah is referred to in the General Assembly minutes above as Deputy Commissary of Purchases (for East New Jersey) during the Revolution. In addition to that role, he also served as a member of New Jersey’s Provincial Congress as a deputy from Middlesex County. In that capacity, he often took messages to and from the Provincial Congress and the Continental Congress in Philadelphia. Here is one example:

Returning to Azariah’s cousin, Nehemiah Dunham continued his public service after the Revolutionary War. He served as a Justice for Hunterdon County until 1801.

Nehemiah Dunham passed away on March 12, 1802, at the age of 80. He left a widow (his fourth wife, Bethany Berdin) and numerous adult children through two previous marriages to Hester Ann Dunn and to Mary Susannah Clarkson. Dunham’s marriage to his third wife, Antje (Ann) McKinney, produced no children, nor did his last marriage to Bethany Berdin. His first three wives all preceded him in death.

Nehemiah Dunham’s will, which he signed and had witnessed on December 16th, 1801, demonstrates that Dunham was an espoused Christian. He included language beyond the standard language of the time showing his faith, where he recommends his “soul to the Great and Almighty God who gave it to me . . . in hopes of a joyful Resurrection through the merits of my Lord and Saviour Jesus Christ.” He was also an early member and trustee of the Bethlehem Church, now the Bethlehem Presbyterian Church at Pittstown, where he is buried. Reba Bloom, “A History of Bethlehem Presbyterian Church Pittstown, New Jersey, 1730-2011” at 9-10 (1980, updated 2007 and 2011). The exact location of Dunham’s grave is unknown. However, church records indicate that he was buried in the Old Bethlehem Presbyterian Church cemetery and he was a 1795 subscriber to the Church graveyard.

The Dunham Slaves

Dunham’s will and subsequent documents prove that he was a slave-owner. Although slightly illegible and difficult to read, the twelfth clause (highlighted below) is where he sets forth disposition as to his “young” slaves.

It reads:

“Twelfth, I give to my son James, my Negro boy Tom, to my son John my negro boy Abe, to my son Aaron, my negro boy Andrew, and to my Granddaughter Susannah Guild, my Negro wench Lydia, until the said negro boys and girl do severally arrive to the age of twenty eight years of age and my will is also that they shall be set free from slavery; and my will is also, that my negro Cesar shall live with my son James, or any other of my children that he may choose to live with and as to my other young negros that is to say, Sarah, Aaron, Dina and Isaac my will is that my executors do put them out to any of my family or to any other good place or places until they several arrive at the age of twenty eight years, at which age I order them to be set free from slavery.”

See Will of Nehemiah Dunham, New Jersey Wills Vol. 40 at 28-30 (proved May 7, 1802) and “Negro Wench” Appendix (hyperlinked). Based on Dunham’s will, it becomes evident that he owned numerous slaves. He refers to almost all of them as boys, girl, or young. It is likely, that Dunham had older slaves as well, but that he is principally conveying the younger slaves through his will–and ordering their manumission.

The fact that he ordered the freedom of his young slaves at age 28 is interesting to me. The law in New Jersey in 1801, when Dunham drafted his will, allowed that slaves could be manumitted without penalty between the ages of 21 and 35. Dunham chose the exact middle of the range for their freedom. Based on the dictates of the will, it is unlikely that children who received the slaves by way of legacy could have kept them longer than 28. But it is an interesting question whether the law allowed them to manumit the slaves sooner.

I have much work yet to do to trace Dunham’s slaves. While many Hunterdon manumissions are online, through the New Jersey State archives, most are not. Instead, they are stored by the Hunterdon County Clerk. As I do not live in New Jersey, I have not yet been able to research them in depth. I want to see if Dunham’s children followed through with Nehemiah’s wishes to free his young slaves at age 28. I also need to obtain a copy of the December 9, 1802 inventory of Nehemiah Dunham’s estate made by Ralph Hunt and Clement Bonnell. This should tell me how many slaves were accounted for as part of Dunham’s estate.

While there is still much to do in order to learn about Dunham’s slaves, there are some relevant Dunham documents online in probate records and through the New Jersey State Archives. From probate records, I learned at least one fact relevant to Andrew. Through his will, Nehemiah Dunham conveyed Andrew to his son Aaron Dunham. However, Aaron died shortly after his father. In Aaron’s November 20, 1802 will, he conveyed Andrew to his brother James. Will of Aaron Dunham, New Jersey Wills Vol. 40 at 163.

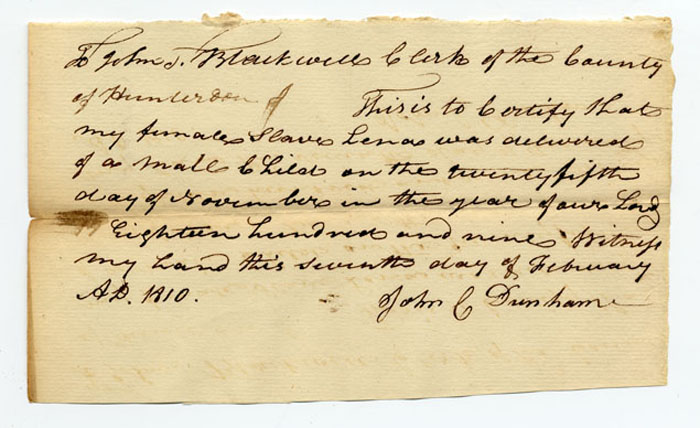

In addition, the State Archives has many (but not all) of the original post-1804 birth records. Through these, I learned that Dunham’s son, John Clarkson Dunham, registered at least 2 births by two different female slaves Lena, who bore an unnamed male (Lena’s son) in 1809, and Reenah, who bore George in 1816. Because of when they were born, after the 1804 act for gradual abolition, Lena’s son and George were born “free,” but as servants to John Clarkson Dunham, to be released upon their 25th birthdays. Lena’s son’s and George’s birth registrations, written apparently, in John Clarkson Dunham’s own hand are below.

In 1818, Dunham’s sons James Dunham and John C. Dunhum entered into an agreement relating to slaves previously belonging to Nehemiah Dunham.

The agreement set forth that John C. Dunham by payment of $200 to his brother James would not be responsible for any “manner of costs expenses & trouble of three certain Black Persons lately owned by Nehemiah Dunham Esq. Late of the Township of Kingwood in the County & State aforesaid . . . the Names and ages of Said Blacks are as follows Cesar aged about Seventy years; Hector aged about Sixty Years, and Dinah aged about fifty six years . . .”

Thus, as of 1818, Cesar, who was mentioned in Dunham’s will, had reached 70 years and was with Nehemiah’s son, James Dunham.

Upon first reading, this contract didn’t make total sense to me. Why was there a property record eliminating John C. Dunham’s obligation to support Cesar in exchange for cash? Was it that expensive to keep a slave? Cesar was 70 years old and likely had relatively few more years to live. Hector and Dinah were 60 and 56.

But a new understanding of the New Jersey laws brings a different theory to mind. Perhaps, James and John wanted to give Cesar, Hector, and Dinah their freedom, but they did not want to do so for a certain period of time. Because of their ages, their owner (remember they were slaves for life), would have to pay a settlement to the overseers of the poor for their freedom. So perhaps, the $200 was to buy the slaves’ eventual manumissions. Until I can confirm with further research, all this amounts to is pure speculation.

In Conclusion

As can be seen, this research is incomplete. There is a lot more work to do. But I have presented it now in hopes of helping just one of the descendants of George or Andrew or Cesar or Dinah or any other of Nehemiah Dunham’s slaves.

I enjoy family-history research immensely. And, in the past, I have taken for granted my ability to freely look up records of individuals in my family tree. The only limitation for me is finding them. Although I knew this abstractly, it has really hit home for me that everyone doesn’t have this same luxury. I am sorry for this, as well as so much more.

As I continue to discover information, I will put information out there about these people who, without any choice, served the Dunham family so many years ago.

I am researching slavery in my ancestry in Hunterdon and Somerset Counties. Thank you for your extensive research. So important to understand.

LikeLike